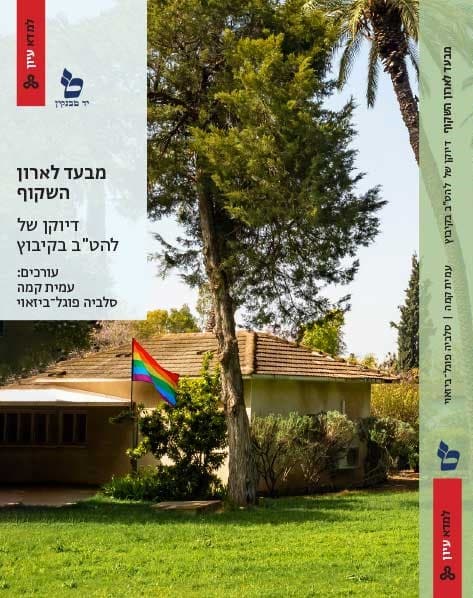

Amit Kama and Sylvie Fogiel Bijaoui

Abstract

Very little is known about LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) in the kibbutz, a 113-year-old intentional communal movement. 182,000 people live today in 268 kibbutzim. Most of the research to date in Israel has focused on LGBT living in cities, especially in Tel Aviv. It is possible that the lack of knowledge about LGBT in kibbutzim is part of the “transparent closet” phenomenon: people know that one is LGBT, but do not want to talk about it or even do not want to know. In light of the lack of research about LGBT life in the kibbutz, many questions arise that seek not only to fill this research lacuna, but also strive to offer insights, perspectives, and new ideas regarding the lives of LGBT individuals who live or formerly lived in a kibbutz. Therefore, in 2019 we established a research group, designed to shed light on this group. This book is the product of our studies, and it attempts to address different issues regarding the kibbutz way of life and the integration of LGBT in this unique fabric. The book unfolds a wide and rich canvas, and seeks to present extensive knowledge, based on various research methods, about LGBT individuals who have integrated their lives as LGBT and as kibbutz members. The studies focus on dilemmas, challenges, advantages, and benefits that enabled or prevented them to live as LGBT individuals within the unique lifestyle of these small communities, some of which are remote from the urban center. The studies also seek to understand the lived experiences and unique needs of the LGBT population in kibbutzim in the past and today. Additionally, the research presented here reflects on the stances and levels of acceptance of LGBT by the rest of the kibbutz members.

The “transparent closet” is an analytical category that has gained momentum during the last two decades. This concept challenges the artificial dichotomy, which has no empirical or theoretical basis, between being “in the closet” and “out of the closet.” The “transparent closet” means that an LGBT individual's gender and/or sexual identity is a sort of an open secret. The secret is known, and it is known that the secret is known, yet it is not spoken about. This means that the secret is not spoken about even if the information regarding one’s LGBT identity is known, even if there has not been an actual declaration (i.e., coming out). The LGBT individual's identity is thus simultaneously tacitly well-known and yet not being openly referred to, as if everyone agrees that the secret should remain implicit. In other words, the closet does exist despite the fact that everyone knows about one’s LGBT identity, and still, everyone cooperates in acting as if they do not know anything. Thus, in the public space, this collective pretending allows members of the community to accept and include LGBT members, while keeping the information unspoken. In private spaces the “transparent closet” creates an equally problematic situation in which LGBT individuals come out, but their parents and/or acquaintances ignore and hide this fact from the community, thus, actually, rejecting them.

The combination of the distinct characteristics of kibbutz as a unique lifestyle – even if it has changed dramatically over the years – in addition to kibbutzim usually being located in the periphery, raises many questions regarding the lives of LGBT individuals in the kibbutz. Among the kibbutz characteristics worth noting are being a small intimate community where everyone knows well each other, a traditional community that shows relatively high levels of conformity, where social supervision and implicit policing are quite prevalent, and a tight system of emotional discipline. In the recent decades, there have been drastic changes to kibbutz characteristics with demographic growth and diversification, privatization processes, individualization, and a decline in the hegemonic status of the communal ideology. Nonetheless, the kibbutz still functions as an independent social unit, significantly different from the city in general and the Tel Aviv metropolitan area in particular, where LGBT life has not been adequately researched.

In light of this, the purpose of this book is to begin filling the gap of the unknown history and to take a closer look at contemporary LGBT experiences in the kibbutz. Based on the assumption that the “transparent closet” is a dynamic and context-dependent category, the book examines different processes over the years that have affected the creation, growth, and decline of the “transparent closet.” Accordingly, we draw a portrait of LGBT life in the kibbutz in different periods. contextualizing the book’s chapters in reference to those developments: (A) The transition from the "classic” kibbutz that required total uniformity and rejected anything it defined as deviance or Otherness, to a more open and tolerant community; (B) The LGBT ‘revolution’ for full social integration and equal legal status in the world and in Israel and its effects and ramifications on the kibbutz. (C) The demographic and social changes in the kibbutz, expressed in institutional and personal individualization. (D) The rural migration, namely the increasing migration from urban centers to rural areas such as the kibbutz. Following this approach, three different periods in LGBT kibbutz life can be distinguished as follows:

The “transparent closet” period: from the establishment of the kibbutz to the 1970s

Very little is known about LGBT life in the first decades of the kibbutz, prior to the establishment of the state of Israel and soon after. In this collective commune, which was practically detached from the urban cities and towns, kibbutz members sought to create a “New Adam" and a "New Eve” in the “world of tomorrow.” In this context, there was no room for Otherness or deviance from the ‘heterosexual and heteronormative model. The intensity of the day-to-day interactions between the members was the basis of the feeling of togetherness and sharing, an anchor of solidarity. Simultaneously, these interactions were also the basis of constant social supervision of the individual's life and feelings. It may be said that the kibbutz did not seek to remove the “deviants”; it mainly sought not to see them or know about them.

Despite all this, it is possible to discern different kinds of “transparent closets." For example, the chapter by Yaffah Berlovitz, Jessie Sampter, Leah Berlin: A queer enterprise story in the first years of the kibbutz, describes a love story of two women, Jessie Sampter and Leah Berlin, who were members of Kibbutz Givat Brenner in the 1930s, where they established a vegetarian sanatorium and shared their lives. Even though they did not hide their love for each other, the kibbutz members did not know how to treat their relationship. As a result, Sampter and Berlin remained in the “transparent closet”: they received ambivalent reactions from their comrades, who defined them as just ’good friends’ and not as a couple. Alongside all their achievements and the respect that they earned, Berlowitz also mentions the feelings of pain, loneliness, and lack of understanding that accompanied their lives since their love for one another was not really accepted.

Haim’s story, presented by Sara Maanit in the chapter, “Who was Haim, that kibbutz member who lived among you for so long?": The life story of a homosexual living in a kibbutz from the days of the youth movement into the 1980s, is about a “transparent closet” where a lonely man, who was financially and psychologically dependent on the kibbutz, was literally imprisoned. This is the story of a gay man who was one of the founders of the kibbutz where he lived for fifty years. Haim requested that after his death the kibbutz members read a letter he left for them. In the letter, Haim points the blame at the kibbutz society in general, and at the members of his kibbutz in particular. Many knew that he was ’different’, but, except for a small number of kibbutz members, no one did anything to take him out of his self-hatred, the shame he felt, and the constant loneliness. Without financial resources and/or a family of his own, he was forced to live a life of lies and pretense.

The following two chapters take us into a different reality, even though they refer to the same period. Dotan Brom’s chapter, “I couldn’t live a double life”: Giora Manor, the kibbutz and the “transparent closet”,refers to the “transparent closet” that Manor lived in for a significant part of his life until the 1990s, when he came out in an interview for a kibbutz newspaper. Manor – a theater director, art critic, and magazine editor – was highly respected. His artistic work allowed him to move away from the kibbutz and periodically live in Tel Aviv and Europe, and there to be himself without too much difficulty. Despite his claims that he could not live a double life, he did in fact live most of his life that way, behind a smokescreen of his open secret. In the last decade of his life, he came out publicly. However, this was at a point when his status was already stable, and also at a time when Israeli society had begun to change. Thus, his coming out did not really endanger him.

The chapter written by Yuval P. Yonay, “The first kibbutznik out of the closet”: Kuka’s gay life in a kibbutz of the late 1960s, describes a unique story that allowed Yitzhak (Kuka) Kaden, starting in the late 1960s, to live as a kibbutz member, a devoted father to his family, and also as a gay man in the kibbutz that he took part in establishing. It seems that his work accomplishments, and the fact that he was seen as a kind-hearted person who was always willing to work for the benefit of the collective, allowed him to actualize himself and to live openly. Besides, Kuka’s open lifestyle was possible because his nuclear family in the kibbutz, alongside whom he actualized his gay identity, did not coerce him into a closet, and also because his kibbutz made a place for these unusual family patterns, without imposing the heteronormative model on him and his family.

Cracks in the “transparent closet”: The last two decades of the 20th century

The 1980s and 1990s were years when the ‘classical kibbutz changed beyond recognition. During these two decades, the transition from sleeping in children’s houses to family living was completed and privatization processes, through which different aspects of kibbutz life transitioned from collective to personal responsibility, grew stronger. Personal or family budgets took the place of the collective budget, while communal services (such as the kitchen, dining room, and laundry) transitioned into individual responsibilities. Simultaneously, these transitions were also accompanied by individualization processes that made the individual's wants and needs a central component in community and family life. In addition, connection with the ’outside world’ became more acceptable, more common, and accessible. For the LGBT community at large, this period saw significant and momentous changes; a time when LGBT civil, legal, societal, and cultural status was becoming more equal and tolerant. Inter alia, in 1988, homosexuality was de-criminalized. Later on, during the 1990s, the collective political identity coalesced among different LGBT groups and laws were passed that outlawed discrimination against LGBT individuals at the workplace, enabled full recognition by the military, and recognized same-sex couples and family. Simultaneously the community started to express itself more freely.

These dramatic changes, despite their strength, had but a small effect on the LGBT in kibbutz, and the “transparent closet” had only barely began to crack. Therefore, it is no wonder that in Ilana Mizrahi-Naor’s chapter, The first generation: Older lesbian kibbutz members, lesbians who grew up in communal child rearing and collective education during the 1950s, but came out of the closet in the 1970s and 1980s, or women who formed their lesbian identity after they had married men and raised children in a kibbutz during those years, indicate that they had positive experiences as lesbians only outside the kibbutz, particularly in institutions of higher education or during their military service. They point out that they had come to full understanding of themselves with the help of feminist organizations, only-women lectures and parties that took place in private homes and clubs, sometimes under a cloak of secrecy, all of which transpired outside the kibbutz. They also report that most of them later left the kibbutz, rebuilt their lives on their own, and experienced successful motherhood. Consequently, in old age, only a small number of them considered returning to the kibbutz, for their painful memories have not been erased.

Notwithstanding the differences between various kibbutzim, Noah Bar Gosen’s study, “Stand by me”: Constructing a gay /lesbian identity in the collective education system in the kibbutz – A retrospective study, indicates a similar situation. Until the end of the 1980s, positive change toward LGBT identity and individuals was not manifested in the kibbutz education system. The process of formation of LGBT identity did not receive special attention from educators or significant adults. This silencing was due to Zionist and collective values that were strengthened and emphasized. As a matter of fact, formation of gay/lesbian identities – were still perceived as alien to the collective identity- and hence evolved covertly. Consequently, gay and lesbian adolescents experienced two parallel processes of identity formation: their kibbutz identity and their sexual identity. The first was conducted openly; the second in secret. These latter processes were thus accompanied by feelings of loneliness, marginalization, and alienation. The gap between one’s sexual identity and one’s kibbutz identity was especially prominent among men in comparison to women. The former describe difficult memories of rejection and insult and generally chose to live outside the kibbutz. In contrast, most of the women chose to live in kibbutzim. It is possible that for women, the kibbutz provides more economic security in comparison to the city. In addition, for women, motherhood is an ‘entrance ticket’ into full equality in kibbutz life.

Dismantling the “transparent closet”: The beginning of the 21st century

Since the early 2000s, it seems that the “transparent closet” in the kibbutz is declining and diminishing. A combination of reasons can explain this: the first lies in the acute changes in kibbutz society that are continuing till now to lower the community ‘walls’ and to increase its exposure to the ‘outside world’. The kibbutz system has become more open to new ideas and to new populations, so that kibbutzim currently have more diverse populations compared to the past. In the first decades of the 21st century, the LGBT revolution has also become more institutionalized through the advancement of LGBT civil rights and through increasing tolerance levels by most of the Israeli population. Likewise, it appears that the deep changes in the kibbutzim make it easier for people to return to kibbutz. These processes make it possible for LGBT today to live in kibbutzim, in some of which there is interpersonal openness and acceptance of so-called Others. Currently, quite a few LGBT prefer to live in a kibbutz rather than in the big city and they remain in the kibbutzim where they were born or return to them.

This picture is found in Amit Kama’s chapter, “You are never alone!”: Current gay men's voices. The dramatic changes that have taken place in most part of the Israeli society in the last two decades regarding LGBT rights, their social inclusion, their political representation, and their media images have permeated the kibbutz. Kibbutz society today is more open and accepting of those who were previously considered as Others. The kibbutz is also nowadays a comfortable platform for absorbing tolerant attitudes towards LGBT. The uniqueness of the kibbutz movement since its foundation until the end of the 20th century was an obstacle for those who did not walk the well-trodden path and did not conform to the strict standards of the collective life. Currently, when ideological, social, and cultural differences between the kibbutz and the city are receding, the sense of Otherness is diminished, and acceptance is increasing. The result is a comfortability with which gay men conduct their lives in kibbutzim.

Despite this, the “transparent closet” has still not been completely dismantled. Zeevik Greenberg, in the chapter, Sense of belonging for gays and lesbians in rural settlements in Israel, indicates the existence of the “transparent closet” in the public space. Certainly, rural settlements, and especially the kibbutzim, have changed in the past two decades. This situation makes it possible for gay men and lesbians to live in kibbutzim and to enjoy the unique way of life there. However, the sense of belonging of gay men and lesbians living in kibbutzim is lower in comparison to heterosexuals’ sense of belonging. Gay men and lesbians who seek to live in rural settlements can live in these communities without the trouble of hiding their identities and are not required to hide pretend otherwise. However, they have to live according to the way of life expected of them, which is characterized by familism and heteronormativity, and as much as possible, without emphasizing their identity as gay men and lesbians in the public sphere. In short, they are expected to live in the “transparent closet” in the public space.

A similar picture emerges from the research conducted by Yael Bar-Tzedek and Gilly Hartal, Liberal LGBTphobia in kibbutzim in 2020, about lesbians and bisexual women living. Their stories paint the kibbutz as a polysemic space, in which LGBTphobia still exists to some extent anchored in a liberal discourse. In contrast to violent LGBTphobia, kibbutz LGBTphobia is not experienced as emanating from hatred and desire to harm. This liberal LGBTphobia expresses conservatism and ignorance, among other things, through use of the concept “Father’s house” to denote a family structure and the framing of the heteronormative family as the only option within of the kibbutz discourse. These preserve the institution of family in the kibbutz in the framework of a patriarchal, heteronormative discourse, at the same time as the kibbutz is home to many families that do not fit this model. Liberal LGBTphobia is expressed in practices such as ignoring lesbian and bisexual women, excessive prying into their private lives, and tokensim, which mask stereotypical and conservative attitudes. Simultaneously, the kibbutz is presented and presents itself as an inclusive and tolerant space. This self-presentation stands in contrast to the outside world, mainly the neighboring cities that are conceived as a LGBTphobic spaces, a construction that preserves the superiority of the kibbutz in the eyes of its members.

The chapter by Sylvie Fogiel Bijaoui, ”One of us”: Kibbutz media discourse on LGBT, also indicates that the “transparent closet” in kibbutzim has not yet been fully dismantled. In her study, articles related to LGBT in kibbutz published on the online newspaper Mynet-Kibbutz are analyzed. The articles are an exceptional phenomenon in the history of the kibbutz, which until recently positioned the LGBT issue in a “transparent closet.” Thus, today, the kibbutz is presented as an open and LGBT-friendly community, where LGBT are successful people, who receive the support of their families and the collective. At the same time, traces of the past have not disappeared, and institutional responses are still lacking for LGBT as children, teenagers, and adults. Fogiel-Bijaoui also points to the fact that the ideological approach of the journalists in the Mynet Kibbutz online newspaper contributes to the presentation of the successful integration of LGBT in the kibbutz because it enables them to describe it as progressive, a sort of ”kibbutz pinkwashing” that makes it possible to present the kibbutz as democratic and liberal. On the whole, as she argues, this kibbutz pinkwashing makes it possible to reduce the “transparent closet” in the kibbutz, but not to completely dismantle it.

As noted above, this book is the first of its kind. We hope that it will encourage further research and public discussions about LGBT in kibbutzim and in intentional communities, as well as in other small rural communities. After all, as seen frequently in contemporary literature, the politics of home among LGBT is a still a topic that requires extensive research.